High-Level Model of Roles for Network Slice (ETSI TS 128 350) Explained

Telecom networks are moving toward 5G and beyond, and network slicing is becoming a key element for offering tailored services. By allowing several virtual networks to operate on the same physical infrastructure, slicing gives operators the ability to provide specialized services for businesses, industries, and consumers.

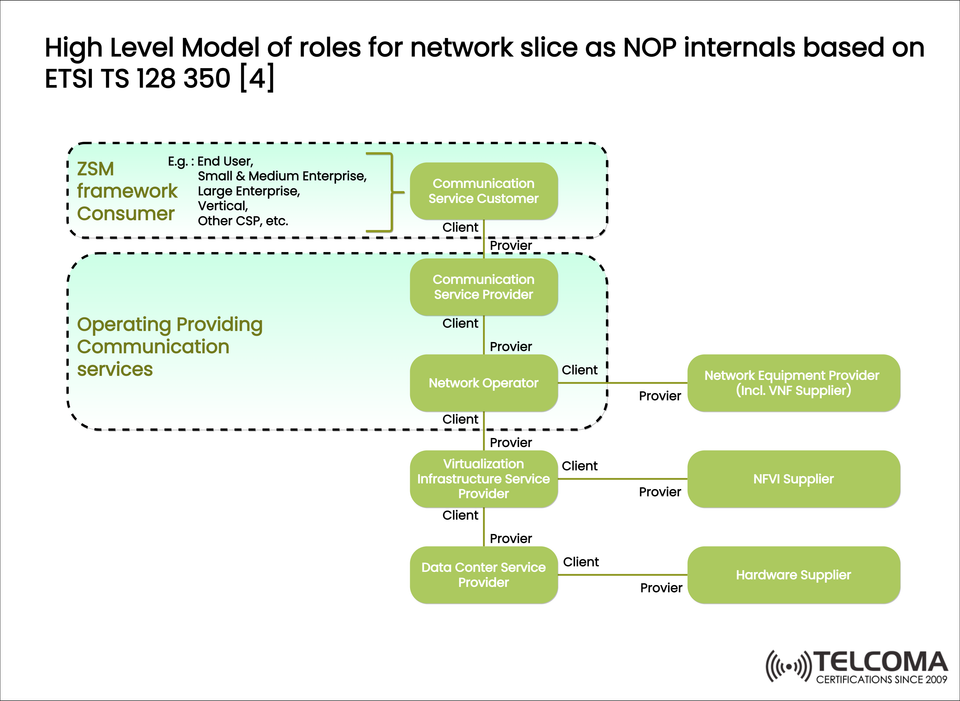

The ETSI TS 128 350 specification lays out a high-level model of roles that shows how different players—like consumers, providers, operators, and suppliers—interact within the network slicing ecosystem. The diagram uploaded illustrates the internals of the Network Operator Platform (NOP), depicting the intricate yet organized relationships among roles in service delivery.

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at the model step by step, outlining the responsibilities of each role and how they connect to make efficient network slicing possible.

ZSM Framework Consumer

At the top of the model is the ZSM framework consumer, which represents the demand side of telecom services.

Examples:

Individual subscribers

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs)

Large businesses

Vertical industries (think automotive, healthcare, manufacturing)

Other Communication Service Providers (CSPs)

These consumers have specific service-level agreements (SLAs) they require, like ultra-low latency, massive IoT connectivity, or high-throughput broadband. They interact with the Communication Service Customer role, which serves as their point of contact within the network ecosystem.

Communication Service Customer

The Communication Service Customer (CSC) is the first role in the ZSM consumer domain.

Acts as the client of the Communication Service Provider (CSP).

Requests network slices or communication services tailored to their business needs.

Defines requirements like bandwidth, latency, coverage, or reliability.

For example:

A business asking for a private 5G slice for its smart factory.

A CSP obtaining wholesale services from another CSP to expand its coverage.

Operating Providing Communication Services

This broader category includes entities that deliver and operate telecom services, featuring several interconnected roles:

- Communication Service Provider (CSP)

Acts as the provider to the Communication Service Customer.

Also a client to the Network Operator.

Responsible for:

End-to-end service delivery.

Service orchestration.

SLA management.

An example would be a CSP offering a managed 5G slice to businesses for IoT applications.

- Network Operator (NOP)

Acts as the core enabler of network slicing.

Delivers communication services to the CSP.

Also a client to:

Network Equipment Providers (including VNF suppliers)

Virtualization Infrastructure Service Providers (VISPs)

Key responsibilities:

Provisioning network slices across RAN, transport, and core.

Monitoring and assuring slices.

Managing interoperability between different domains.

- Virtualization Infrastructure Service Provider (VISP)

Supplies virtualized computing, storage, and networking resources.

Acts as a client to the Data Center Service Provider and a provider to the Network Operator.

This role is particularly important in cloud-native 5G environments where VNFs (Virtual Network Functions) and CNFs (Cloud-Native Functions) operate on virtualized infrastructures.

- Data Center Service Provider (DCSP)

Offers data center hosting and facilities.

Acts as a provider to the VISP.

Ensures physical resources like hardware, power, and cooling for virtualization infrastructure.

Together, the VISP and DCSP create the infrastructure layer that supports the operator's service platforms.

Supplier Roles

To support operators and service providers, the model includes supplier roles that feed into the ecosystem:

- Network Equipment Provider (NEP)

Supplies network components, functions, and VNFs.

Acts as a provider to the Network Operator.

Examples include 5G RAN equipment and mobile core functions.

- NFVI Supplier

Provides the Network Functions Virtualization Infrastructure (NFVI).

Collaborates closely with the VISP to deliver cloud platforms that can host telecom workloads.

Examples include VMware and OpenStack distributions.

- Hardware Supplier

Supplies the physical hardware components used in data centers and NFV infrastructure, such as servers and networking gear.

Acts as a provider to the Data Center Service Provider.

Client-Provider Relationships

The diagram depicts a hierarchical chain of client-provider interactions:

Consumers → Communication Service Customer → Communication Service Provider → Network Operator → VISP → DCSP → Suppliers

This layered model ensures a clear separation of responsibilities, allowing for modular service delivery. Each role consumes services from the one below and provides them to the one above.

Key points:

Clients demand resources or services.

Providers deliver them while meeting agreed SLAs.

In practice, roles can overlap (like a CSP also functioning as a network operator).

Importance of ETSI TS 128 350 Model

The ETSI model offers various advantages for telecom ecosystems:

Clarity of Roles: Standardized definitions minimize confusion in complex environments where multiple parties are involved.

Flexibility: Supports different deployment models, whether single-operator, multi-operator, or federation.

Interoperability: Facilitates integration across multiple vendors and domains.

Scalability: Allows for the seamless expansion of network slices across different sectors.

Business Enablement: Helps clarify B2B and B2B2X relationships in network slicing.

Example Use Cases

Enterprise 5G Private Networks

Enterprise acts as a CSC.

CSP provides a private 5G slice.

Operator provisions and manages the slice using VISP and DCSP infrastructure.

IoT Connectivity Services

IoT service provider uses connectivity from a CSP.

Network Operator provisions IoT-specific slices tailored for considerable device density.

Cloud-Native Telecom Networks

VISP delivers the platform to host CNFs.

NFVI and hardware suppliers provide high-performance infrastructure.

Challenges in Real-World Implementation

Even with a clear structure, there are several challenges:

Complex Interdependencies: Coordinating SLAs across numerous roles calls for strong collaboration.

Vendor Lock-In Risks: Operators must maintain open interfaces to avoid reliance on any single vendor.

Security Concerns: Multiple parties involved increase the risk of data breaches or cyber threats.

Operational Overhead: Balancing legacy infrastructure with virtualized or cloud-native setups can be tricky.

Conclusion

The high-level model of roles for network slicing outlined in ETSI TS 128 350 provides a roadmap for telecom operators, service providers, and suppliers to work together more effectively. By clearly defining roles for consumers, providers, operators, and suppliers, it establishes a structured ecosystem where network slices can be provisioned, managed, and optimized.

For those in the telecom field, grasping this model is key to rolling out scalable, secure, and business-ready 5G network slicing solutions. It makes sure that everyone—from businesses to CSPs, operators, and equipment vendors—plays their part in delivering seamless connectivity.

In summary, ETSI’s model connects the demand for customized services with the intricate telecom supply chain, paving the way for practical solutions in zero-touch automation and network slicing.